What Is Diastasis Recti?

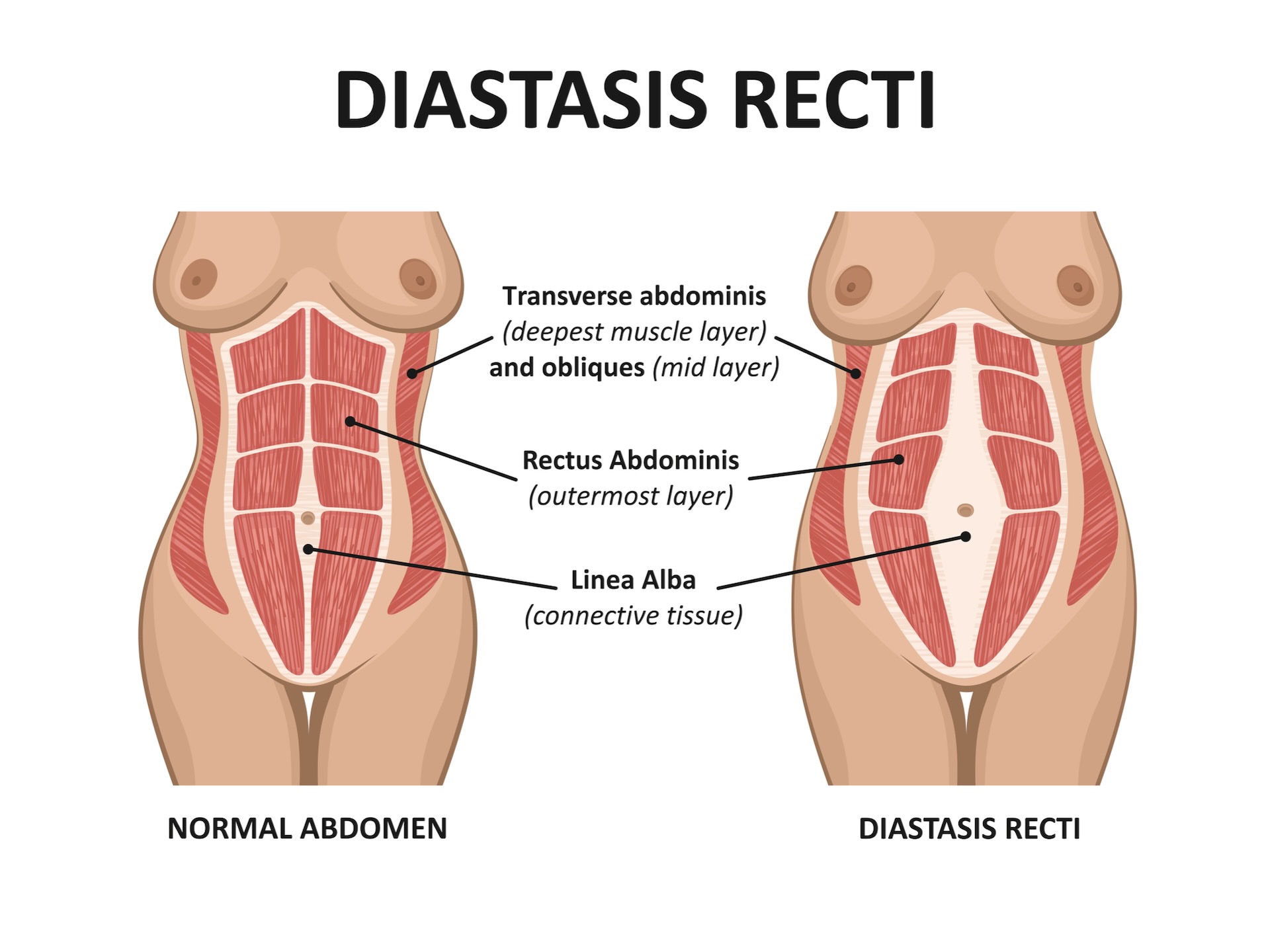

“Diastasis,” originating from Greek, signifies “to divide” or “to separate.” Consequently, “diastasis recti” or “rectus divarication” refers to the parting of the rectus abominus muscle, commonly known as the abdominal “six-pack.”

Within the abdomen, there exist paired sets of rectus muscles on the left and right sides, interconnected at the centre by a line called the linea alba. The divergence of these muscles from the linea alba leads to a relative thinning at the midsection, noticeable as a protrusion, when sitting forward from a supine position.

Is Having Diastasis Recti Serious?

Diastasis recti should be clearly distinguished from a hernia. Unlike a hernia, diastasis recti does not involve any opening in the abdominal wall through which organs might get entrapped, and it typically lacks associated pain. Generally, there’s no pressing medical necessity to rectify this condition. However, in certain cases, patients might encounter back pain. This discomfort arises from the disturbance and imbalance of the core muscles encompassing the abdomen and back. Any disparities in this region can potentially lead to discomfort.

If you have an abdominal wall hernia alongside diastasis, it might be advisable to undergoing a procedure to address both the diastasis and perform hernia repair concurrently. This approach could potentially enhance the outcomes of the hernia repair as well, and prevent further herniation in other areas of the separated linea alba.

What Causes Diastasis Recti?

Diastasis recti can manifest in both males and females, with a significant hereditary aspect determining susceptibility to this condition. Furthermore, repeated stretching or strain on the abdominal muscles can induce diastasis.

Among women, pregnancy stands as the primary cause. As the rectus muscles elongate away from the central line during pregnancy, they might not return to their original position after childbirth. This phenomenon is particularly observable in pregnancies involving multiple births (such as twins or triplets), and it’s also noticeable after subsequent pregnancies. Diastasis in such scenarios often localizes around the midsection or extends from the upper to lower abdomen.

In men, diastasis tends to predominantly manifest in the upper abdomen. It is usually the result of accumulation of intra-abdominal fat (metabolic syndrome). The outcome is a rounded or barrel-like appearance in the upper abdominal area rather than a flat surface.

Is There Anything I Can Do To Help With Diastasis?

Reducing the abdominal circumference and engaging in core-strengthening exercises are the principals in managing diastasis recti. In patients with central adiposity due to the accumulation of intra-abdominal fat, it is imperative that they lose this weight to reduce the abdominal circumference. One the abdominal girth is reduced, the exercises play a pivotal role in diminishing the bulge’s size and mitigating the likelihood of further separation of the muscles. The primary emphasis of the exercises lies on the transversus abdominis muscle, often referred to as the inner abdominal girdle. These exercises target this muscle, aiding in the realignment of the rectus muscle towards the midline.

There are, however, some exercises that are best avoided – in particular:

- Exercises involving reclining or leaning back using a Swiss ball.

- Yoga poses that involve stretching the abdomen, like backbends.

- Abdominal workouts that require lifting the upper spine from the ground, such as oblique twists and crunches.

- Pilates and reformer exercises incorporating positions like head float, upper body flexion, double leg extensions, planks, or 100s.

- Activities leading to abdominal bulging during exertion.

- Lifting or transporting heavy weights.

The most commonly prescribed exercise programme for the treatment of diastasis recti is the HEXACORE Program. The foundation of the Hexacore philosophy revolves around the pivotal aspects of core training and support for both men and women. The program is comprised of the following exercises, specifically designed to enhance core strength and assist with the management and symptoms of diastasis recti.

1. Core Engagement

Sit in an upright position and rest both hands on your abdominal area. Inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand, and sense the movement beneath your hands. As you exhale, activate your abdominal muscles, envisioning a gentle pulling of these muscles towards your spine. Sustain this engagement for 30 seconds, all the while maintaining a steady breath (avoid holding your breath). Subsequently, execute 10 additional slight contractions before releasing the muscle tension.

2. Sitting Contraction

Adopt the same seated position as in Step 1. Place one hand on your upper abdomen and the other below your navel. Inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand. Upon exhaling, engage your abdominal muscles, aiming to draw them further towards your spine. From this initial point of engagement, intensify the contraction slightly, pulling your abdominal muscles even closer to your spine. Maintain this heightened contraction for 2 seconds, then revert to the initial contracted position. Repeat this sequence 10 times.

3. Head Elevation

a) Lie on your back, knees bent, and feet flat on the ground. Inhale, letting your abdomen expand. As you exhale, draw your abdominal muscles inward toward your spine.

b) While maintaining this abdominal contraction, tuck your chin and lift your head off the floor. Keep this position for 2 seconds. Then, gently lower your head back down to the floor. Repeat this sequence 10 times.

4. Vertical Push-Up

a) Stand at arm’s length from a wall and press your palms flat against it. Inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand. Upon exhaling, engage your abdominal muscles, pulling them towards your spine.

b) While maintaining this abdominal contraction, perform a push-up against the wall, ensuring your elbows remain close to your body. As you push back up, intensify the contraction of your abdominal muscles, drawing them even closer to your spine. Repeat this sequence 20 times.

5. Wall Squat

a) Position yourself with a sizable exercise ball between your back and the wall. Step a comfortable distance forward, setting your feet hip-width apart. Inhale, permitting your abdomen to expand. As you exhale, engage your abdominal muscles by drawing them in towards your spine.

b) While maintaining this abdominal contraction, flex your knees to lower into a squat position. Upon extending your legs to stand, heighten the contraction of your abdominal muscles, pulling them even closer to your spine. Repeat this sequence 20 times.

6. Squeeze Squat

a) Position yourself against the wall, taking a step forward. Insert a compact exercise ball or a firm pillow between your knees. Inhale, allowing your abdomen to expand. Upon exhaling, activate your abdominal muscles by pulling them towards your spine.

b) While maintaining this abdominal contraction, lower yourself into a squat position by bending your knees. Subsequently, press the ball or pillow between your thighs, concurrently intensifying the contraction of your abdominal muscles, and sustain this for 2 seconds. Repeat this sequence 20 times before returning to a standing position.

These exercises will not only help to prevent disruptions and injuries to the core but can help to foster optimal post-surgery outcomes, in patients following abdominal wall surgery, with a specific emphasis on core restoration.